A RE:ENLIGHTENMENT REPORT

Towards a New Platform for Knowledge:

The Future of Enlightenment

t is often said that we are all heirs of the Enlightenment. Although there are different ways of understanding this observation, and indeed many ways of contesting it, it nevertheless remains the case that we live with the legacy of what happened 250 years ago when the tools, methods, and institutions for human inquiry in the West were recast and re-configured. We continue to inhabit those institutions and deploy many of those tools: our modern universities and schools, libraries and museums, learned societies and clubs, periodicals and procedures were all given definitive shape during the Enlightenment. Since that time both gradual and sudden changes in technology, finance, and society have exerted pressure on the forms and shapes of knowledge that emerged from the Enlightenment. But these pressures have been variously resisted or welcomed, in some areas destructive in others beneficial: if we live within the legacy of the Enlightenment it is precisely a legacy, something we care for at the same time as use for our own, contemporary, purposes. The Re:Enlightenment Project was formed in order to participate actively in the future of Enlightenment—preserving, adapting, testing Enlightenment ways of knowing the world and ourselves— in order to ask what can and should Enlightenment look like now?

The querying already underway of certain norms and practices—from the physical storage and display of knowledge in libraries and museums, to its packaging into print in journals and books distributed through commercial and university

presses, to the foregrounding of empiricism, measurement, and reductionism in scientific research—can be understood as initial gestures toward that future. While some of these attempts to work on, but still within, the legacy of the Enlightenment have made progress— the substantial literature that seeks to establish the precise shapes and forms of Enlightenment itself represent one of the most consistent efforts to do this—we have been reluctant or unwilling to connect together the different ways in which these attempts have been made. We have failed to join common cause—bringing the museum into the research university or taking the university out to the world—in our continuing address to the question ‘what can and should Enlightenment look like now?’ And in the midst of this we suddenly find the landscape being re-configured as financial pressures swiftly intervene.

As funding streams dry up or change channels, the institutions charged since the Enlightenment with the production, curation, dissemination, and accreditation of knowledge, find themselves on the defensive. But what if we engage this near-term crisis—precisely because of its immediate severity—as an opportunity to foster now the common cause that we failed to muster in the past? The Re:Enlightenment Project seeks to redirect the force of forced economic change into a collaborative reassessment of our inheritance, starting with the part of that inheritance in which we all have a share: the overall organization of knowledge that emerged

from Enlightenment. In beginning here we note that its more or less settled divisions within and across narrow-but-deep disciplines—indeed, the concept of disciplinarity itself—has become unsettled. Our recent fascination with ‘inter-disciplinarity’ is one symptom of the remediations in knowledge that are already occurring. We see it as well in remediations of scholarly practices, like the demise of the scholarly bibliography or the concordance, as scholars embrace the database and the search engine.

At the very least these efforts will result in a new set of relations—hierarchical, predatory and policing—between disciplines. But there is also the possibility that a strenuous interrogation will lead to a reconceptualization of “discipline” itself—and thus allow us to query the continuing usefulness of disciplinarity as a way of organizing what is known and knowable. One primary aim of the Re:Enlightenment Project is to model and test alternative accounts of the field of knowledge as a whole, its mediations and hierarchies, in order to provide possible new conceptualisations of how we can divide and organize. We seek to do this by insisting that any such re-conceptualisation must take full account of the complexity of the field of knowledge once it is seen through the modalities of curation, production, dissemination, accreditation and transformation which determine specific practices within specific locales. We call this congeries of actors, practices and locales ‘the siting of knowledge,’ since we wish to underscore the fact

1

that knowledge is always located: it feeds off and into institutions, practices, traditions, and lineage.

To recognize all knowledge as sited knowledge is to recast our understanding of how knowledge works in the world—of how the field of knowledge consists not just of different kinds but also of manifold nodes and clusters of sites for both knowledge and knowing. Each of these sites determines what is and can be understood as knowledge from its own location, and each of these sites is always already operating in relation to other sites, sometimes in strenuous and productive linkages—where connection is mutually supported—and at others in tension and occasionally unproductive antagonism. The Re:Enlightenment Project seeks to bring into the open the protocols that enable and disable connection, including disciplinarity itself as a protocol for making or preventing connections among sited knowledge. From this perspective, both the inflexibilities of disciplinary formation and the limitations of inter-disciplinarity become more apparent.

It is clear that in the historical Enlightenment those sites were connected in ways different to how they are today: the museum, as a ‘siting’ for the production of knowledge, was not held in the same relation to the Enlightenment university as it is to the contemporary research university. Privately funded research laboratories – think here of the Bowood group (of Shelbourne, Priestley, Price, etc)—were connected to public or royal institutions in very different ways than today’s research centres

and laboratories. The Re:Enlightenment Project seeks to use our reflection upon these historical differences as a means for interrogating the current configurations of the sites of knowledge. We wish to identify where there may be impediments to the re-connection of, say, the museum with the research institute, or where there may be advantages to innovative ways for institutions to co-inhabit each other—such as the university and the museum—without fear of being co-opted into a single, unwieldy entity. This may encourage the creation of hybrid institutional forms that may enable the emergence of a de-disciplinary configuration of the field of knowledge—a configuration that connects the nodes and clusters referred to above without being routed through disciplinarity. This would be a new siting of knowledge.

The pressures for change of some kind are not only financial and organizational; we are concurrently experiencing a revolution in mediation that promises to be as significant as the early modern move from oral and manuscript forms to print culture: the conversion of analogue forms of knowledge into digital formats. Although this transformation appears to be touching every area of human inquiry, we have, as of yet, made little headway in comprehending the possible consequences: will change of this kind and on this scale enable new and different kinds of knowledge to emerge? What is the remainder of the conversion of analogue to digital?

This mutation in mediation– pervasive though it already is in respect to print culture – may be at its most telling in the arena of objects and intellectual practices. Many museums and galleries are already well advanced in the translation of their archives of things, with their analogue catalogues, into a new kind of collection, where what is known and knowable about those things is mediated by digital code. This change in format has encouraged the development of protocols for manipulating and analysing these new data streams. Moreover the continuously increasing capacity for data management, retrieval and manipulation opens up what and how we know the world and ourselves to new interrogation. And, crucially, the scale of information processing—in content and in speed—is exponentially in advance of any analogue system previously known. It may not just lead to something like a cross fertilisation of already extant fields of enquiry – say the ‘digital humanities’ – but to the creation of entirely new areas for exploration. Fast and complex computation will complement, alter, or supplant human understanding in ways that we cannot predict. These new kinds of thought, in turn, may render the disciplines impractical or unhelpfully inflexible. At the very least what looked like a sensible way of cutting up the field of knowledge to our analogue forbears will seem like an arbitrary division of the terrain of investigation to our future selves. In a sense this digital mutation will return us to the period of the Enlightenment when the field of knowledge was comparatively fluid and the partitions within which that knowledge appeared were still permeable.

2

The pressures identified above—financial downsizing and the pressures our own changing practices are exerting upon knowledge and its institutions—will be likely to create a new landscape within which knowledge operates and is made visible. New configurations of existent practices and institutions will, we believe, emerge, mutations of current hierarchies will take place, and new sites for the production, curation, dissemination, accreditation and transformation of knowledge will be produced. What we are calling the siting of knowledge will evolve. To guide us through this contemporary terrain without wandering into the desert of pure, ungrounded speculation, we have adopted as our initial, signature strategy a turn to the historical Enlightenment.

In that turn from present to past (the first of our touchstones), we gain access to a long view of the history of mediation, to the opportunities and pressures of new technologies (the second touchstone), to the potential for new institutional and disciplinary connectivities (the third touchstone). Our aim is not to reproduce the historical Enlightenment but to work with our understanding of the siting of knowledge in order to have a stake and a say in its imminent reconfigurations. The Re:Enlightenment Project seeks to report, retrospectively and prospectively, on our new landscape, knowing that we cannot specify fully the precise contours of knowledge while insisting that, at our peril, we neglect to take responsibility for shaping them.

Through its Exchanges, The Re:Enlightenment Project has been at work materializing a more inclusive and vigorous we—a collaborative we fueled by the diverse energies and expertise of different kinds of institutions. In its research efforts, the Project operates with methodologies and analytic practices—what we term a ‘forensics’—that are intended to be organic, using feedback mechanisms that ensure the continuous evolution of the Project. As we learn more about what enables and what blocks collaboration among sites, we seek to feed this knowledge back into our account and our practice.

This report, then, must be retrospective in achievement, but it is prospective in aspiration. Our tools of analysis are subjected to pressure for change or mutation as the account evolves, just as our protocols for description alter in the face of new objects for enquiry. Thus, we use an organic forensics that is fully embedded in an organically evolving research project: a research organism. In our evolution to date so far we have identified two key terms that enable us to comprehend the siting of knowledge, both in its historical forms and in its present configurations, in ways that may be transformative. Any such transformation will be both analytical, leading us to new ways of understanding both the past and the present, and conceptual thereby providing the means for future reconfigurations of the sitings of knowledge. Those two terms are the operating platform and the exchange.

Our turn to the first term is intended to make us aware that disciplinarity is only one kind of operating platform, albeit the dominant one since the Enlightenment. In the case of the second, the exchange, this term is used to highlight the fact that connection and connectivity are the primary drivers for enabling communication between and across distinct sites. Our use of the term exchange is also strategic: by engaging in the practice of the physical, human exchange as we did in New York and are now doing in London, we seek to reconfigure the operating platform for knowledge. Or, to be more specific about these first steps, we seek to unseat disciplinarity through our experiments in exchange.

The Operating Platform

At its simplest, as a physical object, an operating platform for knowledge can be understood as a table or lab bench where materials for research—books, notebooks, experiments, field-work, objects, subjects, etc.—are assembled, manipulated and interpreted so they can yield new knowledge. Conceived more broadly to include the technological and social infrastructure that provides the foundations for investigation, the operating platform provides the means for understanding the architecture that stabilises the work of sited knowledge. That architecture is both ideational and physical—it supports both institutions and practices as they connect in siting knowledge. The operating platform allows us to see that such connections are

3

driven and regulated by protocols. The connections that are established, enabled, or disabled by the operating platform delimit what can be known and identified as knowable.

The work performed on this platform—from the practices and procedures of the researcher to the translation of research findings into audience-specific genres such as exhibitions, catalogues, articles, and books—is currently shaped by disciplines or by task-oriented configurations of expertise—e.g., legal, medical, and institution-specific—informed by them. Since the late eighteenth century, disciplinarity has been the primary operating platform for sited knowledge, and specific disciplines can be understood as the programs that run on that platform. At different moments and in different contexts, the boundaries between disciplines have appeared to be—or been experienced as— more or less permeable. Although the recent rash of ‘inter-disciplinary’ initiatives appears to push particularly hard against those boundaries, we believe that this development is unlikely to alter the operating platform in ways conducive to a new siting of knowledge. Such efforts often connect pell-mell for short-term ends—and too often the longer-term end turns out to be shoring up what we already have. The weakness of interdisciplinarity is that it does not disturb disciplinarity itself. In its gestures toward connecting disciplines, it leaves untouched the assumption that “discipline” is the form that should organize the field of knowledge—either directly, as

in the Arts and Sciences within universities, or indirectly, as building blocks for the alternative configurations cited earlier.

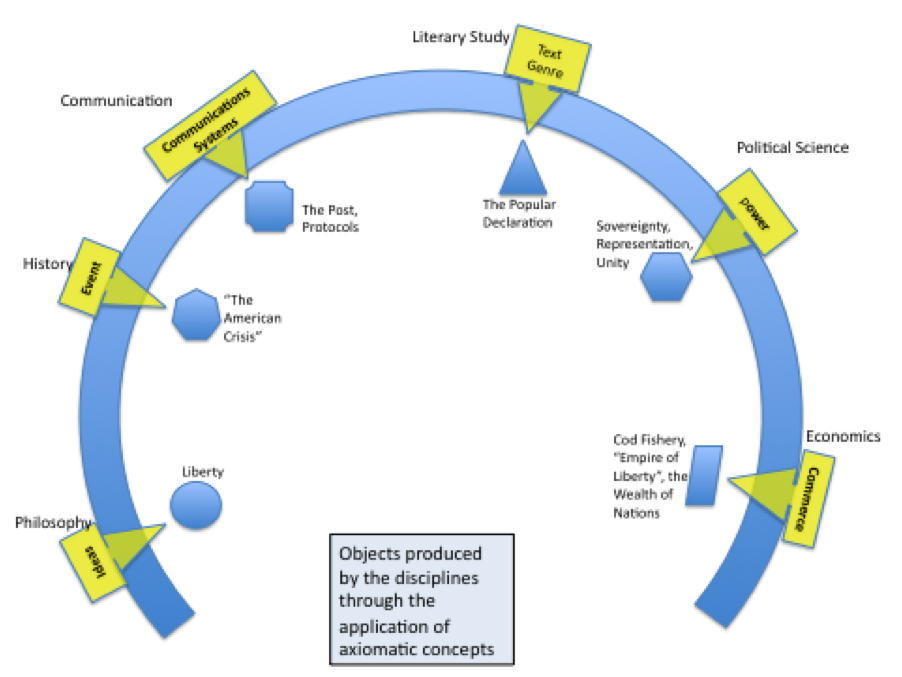

What keeps that assumption in place are the routines of disciplinary practice. Each discipline develops a horizon of questions and goals, a privileged set of matters of attention, and methods to study them. They operate by applying discipline-specific concepts to an area of inquiry in order to generate and stabilize objects of knowledge. For example, to study the American Revolution/ American War, historians have applied certain concepts—event, fact, temporality, causation—to the archive so as to isolate specific objects of knowledge: “the American Crisis,” imperial administration, the dynamic of events that lead to revolution and war, etc. By contrast, a political scientist might use another set of axiomatic concepts—politics, power—to isolate certain objects for study: the institutions of town/county meeting/ provincial assembly, or, the vexing political issues of representation, sovereignty, unity. Economic studies of the Revolution, invoking the concepts of production, consumption and exchange, might focus instead upon the North Atlantic trade or the Whig ideal of ‘an empire of liberty’ founded upon the notion that free exchange increases wealth. Philosophers studying the same revolution might use the concept of the idea to disclose a distinctly ‘neo-Roman’ theory of liberty or a republican notion of action. Communications and media study, using concepts like communication, networking, or

media, might study the newspapers linked to the postal system as agents of change. Finally, literary scholars of the Revolution might use the concept of genre to trace how the American Whigs of British America overwrote the traditional petition of authority with a generic innovation, the popular declaration.

What legitimates these kinds of knowledge as disciplinary knowledge is the modern logic of specialization: the payoff for narrowing our focus is depth of expertise. Disciplinarity valorizes knowledge that is narrow-but-deep—that presents itself as emerging from the confines of a discipline. Disciplines thus make proprietary claims upon the objects they produce and analyze. But what if—in an effort to be “de-disciplinary,” to move “from” the disciplines as the standard form for knowledge—we separate their proprietary claims from the mediations those disciplines perform? One form of mediation would then not exclude other mediations; we could then welcome that multiplicity rather than having to excuse it as ‘inter-‘ or ‘trans-’ disciplinary. Our multiple mediations may then produce new connections between old objects as well as new and different objects. If we understand discipline-specific concepts as mediations instead of the proprietary tools of particular disciplines, we could use our disciplinary training without being delimited by it.

We can represent what has changed in this opening of the disciplines to each other by arranging our

4

sample disciplines in an intra-planar array, as a horseshoe. We avoid circles because we don’t want to encourage the illusion that there is an absolute center of knowledge. In this ‘horseshoe of knowledge,’ the processing through discipline-specific concepts is understood not as the proprietary activities of individual disciplines but as mediations that create objects that are then open to a second order analysis. Here, the term “mediation” is broad enough to accommodate and comprehend a) all of the concepts of the disciplines (event, ideas, communication, genres, power, commerce) and b) the many objects these disciplines (through their various filtering and specifying operations) generate (like crisis, liberty, protocols, declaration, etc.). It is a horizon that can gather objects from all the disciplines, but then articulate their relation in a new way.

“New” in this sense does not mean leaving behind the methods and interpretive tools of the earlier disciplines to create a completely new discipline;

this is not a matter of creating one Inter-discipline, with a capital “I.” Nor does it entail importing objects of study from other disciplines into one’s own discipline, as in “interdisciplinarity.” The point here is to engage in multiple mediations by going out to the objects of concern, drawing from the databases and tool boxes of the traditional disciplines in a heteronymous fashion that may appear opportunistic and strange, fraudulent or dilettantish to those who insist upon the proprietary practices of disciplinarity. But that insistence is grounded in an assumption generated by the disciplines themselves—the assumption that deep knowledge and proprietary knowledge are one and the same. We turn to mediation to raise the possibility that what was once historically sealed can now be pulled apart.

Any new operating platform for sited knowledge must in some way sustain this effort to reconfigure the relations between deep and proprietary knowledge, capitalising on the insights of the former while mitigating the narrowing tendencies of the latter. Although a new platform might be new only in its configurations—a new set of connections or networks to be established between sites of knowledge—it is more likely to be new on account of the deployment of different concepts, in some cases mutations of earlier concepts, such as mediation, and in others completely new. A platform may, like an interface running on software, have its settings and connections configured in many different ways, for agility and flexibility are signal traits in moments of change.

By arguing at this moment for the pertinence of a non-disciplinary operating platform, we are suggesting the utility of developing a new analysis and description of knowledge formation. To do this, we need a more detailed grammar of conceptual forms which explains the different modes of concept use while taking account of the fact that concepts are only fully conceptual when they become shared or common property. When conceptual forms are widely disseminated or used they are no longer only mental entities but also cultural entities. We may also need to build new concepts, culturing them—that is, putting them into circulation and honing their uses in order for them to be commonly available. This second aspect of building new concepts takes us from the strictly ideational to the practices of communication and sharing worlds.

It is far from coincidental, then, that the second term we wish to highlight, the exchange, ushers our argument from the ideational to questions of strategic practice—of how to conduct an exchange, including this exchange. We take this to represent a significant advance on answering the question: “how can one change an operating platform, especially one as entrenched as disciplinarity? The answer, then, is that we must build new concepts, which entails both articulating a new conceptual form—or revealing a new conceptual grammar—and producing and engaging in practices which put these concepts into circulation.

5

The Exchange

We propose the concept of the exchange as a means for understanding how connections can be made within and across sites of knowledge. There are three distinctive ways for thinking how exchange articulates sited knowledge. In the first an exchange is mechanical and rigid: a telephone exchange comprises an array of switches and relays for effecting the transfer of packets of information around a network. In the second an exchange is plastic and dynamic: a stock exchange reconciles supply and demand through the operation of a market calibrated by price. Stock markets are constantly in motion as buyers and sellers reconcile their positions. In the third an exchange is transactional and organic: the human interactions that comprise an exchange of opinions or views are recursive. This kind of exchange must constantly adapt to the flow of conversation, effectively re-configuring the connections that allow one person to see the point of the other.

Exchanges in all three senses provide the location for making connections: individuals around a distributed network, buyers with sellers, one world view with another. Connectivity determines the outcome of movement around the field of knowledge and within specific locales or nodes. If one were to describe this from the point of view of disciplinarity that movement is regulated and policed by specific disciplines, the programs that run on the platform. If one wishes to increase the fecundity of any specific site of knowledge one way of doing so is to connect it to other sites. That is

how inter-disciplinarity most commonly works. And such connections co-aggulate into networks that join together nodes or clusters that are configured in ways to allow connectivity.

Both an exchange and its network forms require protocols to enable the flow of communication around them, and such protocols can become more or less useful for the purposes to hand: the construction of a site of knowledge. Protocols can be as simple as our taking turns in speaking at a meeting or our adhering to address conventions when posting a letter. Protocols enable and constrain communication both internally and externally. By attending to the protocols that give an exchange shape and coherence, we can better understand the workings of past and present sites of knowledge. We may also be able to construct new and different exchanges by specifying the protocols that enable their operation thereby making new connections across the field of knowledge. Protocols, however, can also operate negatively, and they can also conflict, meaning that connectivity cannot be taken for granted. There are gains and losses in any economy predicated upon exchange. Nevertheless exchange is the risk we take in hopes of cultivating newly located knowledge.

How, then, can we minimize that risk? How can our practice of the exchange open lines of communication between sites of knowledge? How can we profit not only from the exchange of like goods—say disciplinary knowledge—but also dissimilar goods? To answer that question we need to return to the three senses of exchange outlined

above. An Exchange provides a flexible way to link human and non-human actors through communication, speculation and interaction. We most commonly think of these linkages as between people—networks of research, for example, are currently conceptualised as networks of researchers, so that activities like the curation, production, and dissemination of knowledge could hardly be thought without human agency. However, an exchange can also connect things: gift exchange takes both physical and non-physical forms. In its physical manifestation the exchange of objects causes the interaction of human and non-human ways of knowing as nodes of knowledge are traded around the floor of the exchange. These interactions can most easily be seen in the work of institutions such as museums and art galleries, where the curation, preservation and interrogation of objects is a fundamental feature of their knowledge practices. However, every form of sited knowledge mediates the connection of researcher with objects: in the library, the archive; in the laboratory, instruments and specimens; in the ‘field’, the recording device and the ‘subject;’ in the seminar room, papers, books & screen. When we consider those sites as both articulated through the concept of exchange and the practice of exchange in its fullest sense, that is in which both human and non-human forms circulate speculatively, we can begin to see how a strategic practice may alter the operating platform, and how we can move from disciplinarity and begin to re-site what is known and knowable.

6

Interdisciplinarity, as described earlier, functions mechanically like a telephone exchange, temporarily linking existing sites. When, however, we shift our senses of exchange from the telephone to the stock exchange, a crucial feature of the latter—speculation—introduces play into the machine, diminishing the need for precisely locating plugs in sockets. Speculation, equal parts hypothesis and fantasy, is also what gives a stock exchange its movement. What we need, therefore, is a way of opening up our current siting of knowledge to the free play of speculation so that the practices of exchange can exploit their potential for fluid and recursive interaction.

This is where our third sense of exchange can be transformative. In this case the connections that are made continuously reconfigure the nodes that are connected. Here the difference between telecommuncation and face-to-face communication is illustrative. In the practical exchange of individual and distinct agential world views the protocols for conversation must be constantly under review. This is how we try to avoid mis-communication and misunderstanding. In such situations we enter a transactional exchange that evolves in real time. This is what we are seeking to do in this Exchange: engage in a strategic practice that seeks to move us from the operating platform of disciplinarity to the future of Enlightenment.

re: “Speculation, equal parts hypothesis and fantasy, is also what gives a stock exchange its movement. What we need, therefore, is a way of opening up our current siting of knowledge to the free play of speculation so that the practices of exchange can exploit their potential for fluid and recursive interaction.”

It seems that work from the field of speculative design (a popular area within human-computer interaction and the ACM’s CHI, CSCW, and DIS venues) is relevant here. There’s some lovely work by Richmond Wong and Deirdre Mulligan at Berkeley that’s more or less on point. Bodhi’s work in speculative fiction also comes to mind. (I’m also doing some work in this area and will happily share it when it’s published. Some of it is currently under review at Journal of Documentation and ECSCW, one is forthcoming at Membrana. Another piece that’s somewhat related was recently published in Personal and Ubiquitous Computing.)

As to the relationship between hypothesis and fantasy, I would suggest Peirce’s theory of abduction. I think I mentioned this in a previous meeting, but Peirce saw abduction as the third form of inference alongside induction and deduction. His writing on the topic is challenging because he never settled on a concrete definition, and the definitions he provided changed over the course of his life. There’s a fine little book about it by K.T. Fann; there’s also a very nice methodological text by Tavory and Timmermans (one of whom, I think, was one of Geof’s students?) that introduces abductive analysis as an evolved form of grounded theory.

I will do my best to attend part of the upcoming meeting, but I’m not sure if I’ll be able to move my schedule around sufficiently.

Really nice to bring out the Peirce, John. Re speculation, I’m between really liking the layers of ‘exchange’ in the text and recoiling against making a stock market metaphor so central. I guess in some ways it’s a happy medium … .

re: “To recognize all knowledge as sited knowledge is to recast our understanding of how knowledge works in the world—of how the field of knowledge consists not just of different kinds but also of manifold nodes and clusters of sites for both knowledge and knowing.”

I am particularly excited to recall, upon rereading, that the group’s initial operationalization of knowledge references its situatedness. Should we be interested in pursuing this line, I think we would benefit from a clearer taxonomy of the Set{Knowledge}.

There is a tendency to speak of knowledge only as formalized Knowledge — the stuff that we produce through disciplinary endeavors like physics, biology, or medicine, in which phenomena are represented as objects that are known and knowable. In this formulation, as Bernhard Siegert would put it, the map becomes the territory because we see phenomena through the lens of the reductionist objects that represent them. We do not study that which is observed, but rather the observation itself (cf Drucker re: the concept of capta).

But, with the increased infrastructuralization of computing — what is generally referred to as ‘ubiquitous computing’ — mechanisms of formal knowledge production bleed into the mundane act of knowing. That is, arcane statistical analyses that occur under the umbrella of ‘artificial intelligence’ or ‘algorithmic whatever’ do not merely produce Knowledge that resides in papers, textbooks, etc. Rather, they produce transient knowledges that pop up in the daily life of the user in such forms as behavioral nudges (cf Thaler & Sunstein; Natasha Dow Schull), recommendations (cf Bart Knijnenburg), navigation aids (e.g, Waze), and even factory-standardized material grammars for family activities (Seberger).

What I’m getting at here is that informal knowing is being colonized by formal Knowledge; the in situ and subjective process of knowing is being colonized by standardized modes of having known (i.e., Knowledge). When we speak about knowledge as situated, we are speaking about something other than the form of Knowledge that we see in, say, the encyclopedic tradition — a knowledge that represents a complete set of the world, like an archive of all possible statements (cf Foucault). So we owe it to ourselves to be more specific about just what kinds of knowledge we are concerned with.

It seems to me that the language of speculation/hypothesis/fantasy that I address in my other comment pushes back against a strictly positivist Knowledge, a definable and limited set of all possible statements about the phenomena-turned-objects of the world. For my money, ‘science’ has won the day: we have whipped the phenomenal world into submission to the map we create of it. And that’s fine. We have benefitted quite a bit from it and will undoubtedly continue to do so.

What emerges as the biggest question in my mind is just what such submission means for the possession and enactment of knowledge at the level of the individual. How do we know in the face of that which is Known? For me, I think this leads to an identification of the limits of Enlightenment. (Dare I say itsends’…) If human achieve maturity through Enlightenment (Kant), then how do we achieve the comparative wisdom of middle age by moving beyond initial maturity? How do we develop a sort of phronesis relative to the importance and appropriateness of knowing vs. Knowledge?

Your final question links to the Whiteheadian or whichever-headian process ontology: step one is to lose the noun Knowledge – it’s always about knowing/process. That’s the next stage (I love having a meta-ranking of Englightenment … it’s like Cantor’s meta-infinities).

A few quick items after my first read (perhaps I’ll have more to say once I’ve given this more thought):

1) I find the introduction of the terms ‘exchange’ and ‘speculation’ especially promising here, as I agree that ‘interdisciplinarity’ has largely failed to produce co-speculation among disciplines (typically instead it reifies disciplinary borders as scholars reach across and grab something for their ‘own’ discipline and bring it back over the wall). I’m thinking in particular of the series of cognitive psychology studies that purport to show that reading ‘literary’ fiction improves theory of mind or ’empathy,’ which cite literary critics from the mid-20th c. (or simply survey study participants about their opinions) to define ‘literary fiction.’ That’s an instance in which the example, in this piece, of historical genre as a contribution from literature scholars would certainly improve our knowledge of the cognitive effects of reading. But it would require *exchange* (in the terms above) as well as a speculative mentality among researchers. My main question on this matter, then, is what institutional forms would speculation take? Or, what kinds of institutional mechanisms would encourage exchange and speculation? My sense is that disciplinarity can hammer these tendencies out of us and reduce curious minds to purposive minds at precisely the wrong point in the research process, but I don’t have a clear sense from above how we’d remedy this at the institutional level.

2) I’m intrigued by the use of ‘forensics’ but could also use a bit more clarity about what work that term is doing in the statement.

3) I’m not sure it’s necessary to invoke the concept of ‘the West’ (at the outset). I don’t mean this as polemical commentary or as a statement of ‘political correctness,’ but rather, if we’re looking to understand the complexities of sited and mediated knowledge and knowledge exchange, then the very coherence of ‘the West’ breaks down, such that the concept might do more epistemic harm than good. To give this a bit more context in light of the statement: I find especially useful the idea of knowledge ‘operating platforms,’ as well as the idea that operating platforms become obsolete (i.e. the obsolescence of disciplinarity in its present form). We might likewise consider the possibility that ‘the West’ (as a concept) is a product of an obsolete operating platform, and that employing it limits our view of the development of knowledge, including during the historical Enlightenment.

Hi Aaron,

First things last – I completely agree with your discussion of the West. It’s a marked term even when trying to demarcate.

Your first comment got me thinking back to the baroque … the rich patrons who funded speculative research. Of course that tradition has not gone away … but it is significantly less central than it was. Some of the tech monopolies have speculative divisions … .

Hi Aaron— I feel like the institutions now are really over, re English. My department is more or less gone. This forum represents to me a new way to have colleagues, and work on new things. I think our future conference badges should simply say: Re.

There are several points in this document where I question the temporality. I’m not sure museums and libraries got locked into their definitive forms at this time … surely they have always been changing, and especially recently more radically. The generic point for me is to celebrate what’s good about the changes that are occurring as well as invoking the crisis.

Hi Geof. Really interesting posts from you and everyone above.

The sense of mutability you articulate in the Whiteheadian process ontology seems concurrent with your preference for the continuous verb form ‘knowing’ above. I like how the dynamic sense might be realised in grammar. But I have three observations about this.

The first is, if we wish to espouse ways of knowing as dynamic states or processes- modes with the quality of kinesis, then this seems to me to present a challenge to the concept of situatedness. In other words, what is a suitable way of conceiving of an historical or cultural boundedness for an epistemology that is mutable and dynamic? It seems easier to ‘situate’ a static ‘knowledge’ in a region or school or institution, but less easy to situate ‘knowing’. Not impossible, but just less familiar to my mind, less easy.

The second is, if we take seriously the idea of knowing as dynamic processes, what are the concrete implications of this? Let us imagine a conference on ‘political knowing in the 18th C’, in which delegates were asked not to use the noun, but only ever the continuous verb. What would that do to the conceptual framework within which delegates were working?

The third is whether we should assume process / mutability / kinesis to some forms of knowing, and not to others. What I find tantalising is the prospect of finding out surprising epistemological truths such as ‘everyone assumes ‘practical criticism’ in literary studies to have highly clear, traditional strategies and ways of knowing. But in fact it is characterised by a dynamism that is absent from more ostensibly mutable modes of literary address’. In other words, those epistemologies assumed traditional may in fact work with highly mutable epistemologies, whereas those assumed to be radical may use (in fact need) highly stable ones.

JR

Lovely points all, John. I think that the concept of knowing as a moveable feast is inherent in the spelling out of the platform above … though that could well be just me.

For the ‘political knowing’ posing the ever-difficult question of what difference a gerund makes … I resonate here with your first point on issues of situation. I think that over-situating has been core to great divides between humanities, social and natural sciences and the arts. Going back to Holton and to some extent Galison it’s easier to conceive of a lot of intefllectual history as practices of knowing travelling between/traversing a number of fields.

The last point is great – I need to think more about it. An immediate reaction. Anthropology has for the longest time been presented as a floating signifier, but is arguably more stable than it would appear to many of its practioners (even with the self-referential turn) – in one locution (ever since we ran out of ‘primitive’ tribes), it’s a discipline in search of a subject … . Whereas sociology has been seen as more stable (everyone from Garfinkel qua ethnomethodologist to mainstream survey researchers claim the unifying tradition of Durkheim).

Anthropology is I’m pretty sure what you might call a war discipline. It has an amazing history embedded in what military people call soft power. Why hasn’t our version (the Re kind) been taken up?

I like the idea of challenges to situatedness. Thinking of challenges emerging here in terms of how knowing/knowledge is stituated–in terms of scale, the individual to institutional has huge implications, and in terms of time, reminding us of that location as well as place.

I like ‘practical criticism’ as an example of how a process rather than knowledge content is the unit at which we consider ideas. There is something dramatic about the protocol: it has roles and rules but the script unwritten; something to hope to emulate. Maybe the reason that prac crit in particular is sometimes seen as traditional is that it has definite roles of student and tutor, which links back to overall questions of the degree to which knowledge is arrived at via consensus or authority.

I love the clarity and urgency of this document … typified by the resonant call to recognize across our many divides what we share and to come together.

A general point which I made earlier so will just adumbrate is that there are already many signs of the changes we want. Thus ‘cohabiting without co-optation’ is I think already happening in a number of places … and has always (cf the Macy Conferences).

I agreed with the statement: “Fast and complex computation will complement, alter, or supplant human understanding in ways that we cannot predict. These new kinds of thought, in turn, may render the disciplines impractical or unhelpfully inflexible.” This is close to Singularity talk – or more interestingly the view that we may use our unique roles as the stewards of understanding. (Hawking years ago talked of theoretical physics being beyond human ken). Understanding should be a community phenomenon.

sorry … speed typing … ‘use our roles’ should be ‘lose our roles’

actually, I’m liking both use and lose here.

When I teach my department’s undergraduate course on the Enlightenment, I begin with a prompt on our online discussion board that asks students “what do we talk about when we talk about Enlightenment?” Even though I use the capital “E” Enlightenment in the prompt, most answers still reference self-help stuff, meditation, etc. before moving on, cautiously, to “maybe the founding fathers” or Voltaire or the age of reason. I know that’s not really our problem. But it is a problem – what the more general public thinks Enlightenment means – when thinking about what Enlightenment looks like today. How or where might the public feature in all of this?

Like Aaron, I like the terms “exchange” and “speculation,” but as I was working through this document I kept getting stuck on the word “institution” (or “institutional”). So we move on from disciplinarity. Good. And we move toward (hopefully) “a collective we fueled by the diverse energies and expertise of different kinds of institutions.” But are institutions not limiting, too, like disciplines – especially when we think about the way that new kinds of knowledge crossed between public and institutional networks in the Enlightenment era? It may be too obvious to ask how and where the general public might feature in Re:Enlightenment. But I think of Addison’s celebration of speculation and exchange in his Spectator paper on the Royal Exchange (not exactly a stock exchange, I know), and I remember that him celebrating forms of exchange that are not merely mediated by price (though price might be the occasion for bringing people together). And I think, too, about all the recent attention given to “public” Humanities, a very rough and perhaps unsatisfying comparison but one that comes to mind nevertheless.

A final, sort-of related point. What would Enlightenment knowledge look like if it went viral and what would virality do to and for that kind of knowledge?

definitely related–and even at a more basic level, what did, does, and could Enlightenment knowledge look like. . even in the Institutions where we are located? I’m situated in a knowledge field that, like your undergraduates, tends to hear Enlightenment and imagine zen, or meditation. And in a discipline, as well as field, that were not yet even imagined in Enlightenment knowledge categories. So this is speculation, and historical data digging, where I’d like to exchange conversation both inside and out.

Once I prepared a reader for my class entitled ENLIGHTENMENT MEDIATION: the copy shop changed it to ENLIGHTENMENT MEDITATION 🙂

The phrase “mutation in mediation” is rich with potential in a number of ways. You might even say numeracy itself plays an important role in the kind of change going on as we revisit Enlightenment knowledge production by way of the media we’re now communicating in. The matter of numbers (adding more things, subtracting others, and figuring out what the new tally of objects might do in dissolving and resolving new disciplines) is implicit in that keyword connected to digital media: “scale.”

Clearly, new technological applications have altered our “intellectual practices” in ways that allow us to grow. We connect beyond institutional confines and geological borders, and equally, across multiple time zones. In the process, change: new ideas come and go. But two overlapping forms of information exchange—or “culturing”—one biological and deadly, the other, technological and lively, have forced a change few of us were prepared for in advance. That too introduces a high-stakes temporal element to the more category-oriented term “mutation,” here equaling the word mutable, which adjoins the words “potential’ and “speculation” not just to knowing more and acting better, but knowing how to stop and start the different ways we might make knowledge toward those ends. It’s hard not to continue thinking in the same way, or to affirm how one’s disciplines are being discontinued, when you have no idea what’s coming next. So, I take the challenge offered in the report to think strategically about making a new knowledge platform to be as difficult as it is distressingly urgent.

While there’s lots more to say about the “intellectual practices” part of having mutated into digital beings, everyone—including those still sticking to the fallacy that literature and computation, like the humanities and science, are knowledge modes permanently assigned to work in the opposite directions—must now affirm at least a little bit of computational literacy. As interesting as that’s bound to become, and as intriguing as it is to link our Zoomed-up teaching and conference modes to the neurological hypotheses that cognition is already a digital process, I’m more curious about working with media mutation as it pertains to “the arena of objects.”

Old materialists used to use the phrase “subject – object adequation” to signal what’s really an inadequate (because alienated and restricted) relationship between humanity and things, wanting in turn to replace what’s commonly recognized as idealism with a better (because organic and expansive) version of subject – object relations. In this better version, the second term becomes both more proximate to the first and more pluralized. More than that, the dash (-) between subject – object gains ascendancy because the tools, technologies, and as the old materialists also used to say, the means of production, are highlighted at the same time. Because the ascendency of the (-) pertains to both modes of knowledge and (or better, as) modes of work, media mutation gets me thinking not only about “supplanting human understanding in ways that we cannot predict” but also about what happens when we rethink the human being per se.

Could we say, the opposite of humanity is not simply the passive, inert, or static version of a thing (old term: commodity; new term: entity), but is instead a vast and hidden situational dynamic (old term: relations of production; new term: mediation), moving subjects and objects closer together in expansive ways? If we did, we would have to get rid of language like “the opposite of humanity,” and a whole host of other poorly conceived “oppositional” discourses, since given our re-working of the subject – object duality, the (-) enlarges the capacity of both terms and shows them to be immanent to each other.

I wonder if there’s something to be learned from notions of set theory, or ideas about genre and disciplines as always mixed, where the superficial division between any two classes of things only looks like an opposition because the more numerous variations shared by the two categories or pointing outwards toward new ones are that are hidden by failing to emphasize the (-): 1 is never unified; and 2 is always more. (Next to Cantor, I’m thinking about what Richard Power’s calls “arborealism” in his fantastic tree novel, The Overstory; or the trillions of gut biomes telling our brains whether or not to generate serotonin; or mycelial exchanges Geoff is interested in; or the “fiction” protocol on the Re: Enlightenment website that turned me on during the last Re:X).

Computation in the broadest sense might be thought about as a mode of knowledge for moving subjectivity beyond its subjectivist shortcomings, putting human beings into beneficial proximity with non-human worlds and changing, by enlarging and exchanging, the attributes of both. To work from here, we’d have to turn Kant’s hypothetical embrace of “all humanity” in what he called a “kingdom of ends” into a more expanded form of “allness,” which can only be found through “speculation” in the “kingdom of means.”

The experiment has progressed mightily in the disciplines I’ve mentioned (neuroscience, botany, biology, science-affirmative fiction), and now dominates the political and economic scenes (human terrain systems in war, bit coin, flash mobbing the NYSE). Where can we find our platform to respond?

Very curious about this idea of genre theory applied to and mixed with disciplines. . . speculating about new possibilities, and about the added value to the set of writings about subject histories and disciplines, which tend more toward individual or binary stories then interactions and intersections . .

Many markets in knowledge exist outside the academic, though the extent to which their infrastructure is more or less academic might well be discussed. I have in mind not only non-academic publishing, independent blogs, the larger book reviews, small journals, in the literary domain, but scientific work in, say, pharmaceutical companies, the computer hardware industry, or audio/visual equipment.

Once upon a time, academic knowledge in the literary fields (and others I believe) was less dominated by the academic cartel. For instance, some of the greatest archival work on Elizabethan drams was done by Chambers, an employee of the British post office. Even now in the USA, the field of American History is more open to non-academic researchers and writers than that of literary study. Literary biography may be the one field in letters that still offers place and prestige to non-academics.

I believe that Re-E would benefit by including researchers and writers who are not academics.

On another line. Although the implications may rule out the use of a key meaning right now or ever, it is true that the German word “Aufklärung” means not only “Enlightenment'” (and “clarification”), it also means ‘reconnaissance.” The term in German keeps not only the general meaning but the military and that of governmental intelligence (e.g. a GDR agency wiith the name). Still, I’d advocate stripping the idea of its German freight and thinking of it in the more neutral, if sometimes military, context of English. The concept is the the point: that of looking around, gaining knowledge by looking again, thinking about recognition and self-knowledge across wide terrain

John – I could not agree more re other forms of knowledge production. This ties in for me with an interest in other ways of knowing – the academic cartel, as you put it so well, is highly restrictive in a lot of fields about what counts as knowledge – it serves to exclude many in our own culture and many cultures which do not work the same way ours does.

Yes.. . the concept of looking around, and of exploring the larger territory would be helpful to all the 4 aspects of knowledge the report points us to.

We too often neglect, and neglect to prepare our students for the tangled webs and threads (per last session) of interdependencies along these lines as well. What Granovetter calls the strong ties hold our attention and recirculate ideas, where the weak ties, with fewer practices and people in common, offer new affordances. And the interdependencies need surveillance and intel –so new scholars are not surprised to discover that reviewer calendars in publishing houses run on quite different schedules from tenure clocks inside the academy.

What Geof calls the cartel ‘restrictiveness’ may have all kinds of unanticipated costs, practical, political, and intellectual.

The Intelligence office of the Stazi was called “Aufklarung”

Returning to The Re:Enlightenment Report a decade later has reinforced my sense of epistemological optimism–the concept we pursued in London at the RSA with Martin Rees and David Deutsch (https://www.thersa.org/events/2015/10/optimism-knowledge-and-the-future-of-enlightenment#). Knowledge solves problems and all problems are soluble. Given all that has befallen us over the last ten years, many have become pessimistic. But to take that turn is to miss the epistemological point and thus the importance of knowledge. Pandemics tell us exactly what Deutsch did: People “are not ‘supported’ by their environments, but support themselves by creating knowledge.” That’s why we need an operating system that facilitates that creation. To discover that the Report laid the conceptual foundation for such a system–with its identifying of the key concepts of “platform” and “exchange”–has reaffirmed to me our Project’s ongoing progress.

I can also report my own progress in understanding the notion of the “siting of knowledge” developed in the Report. It can help us to break out of the binaries that confound so many debates about knowledge: e.g., knowledge as progress vs knowledge as constructed or relative. Siting calls our attention to (the phrase is Mark Algee-Hewitt’s from my recent Zoom with him) the conditions of possibility for knowledge: what kinds of knowledge are possible in what conditions? To be on the platform of disciplinarity, for example, both enables certain kinds of explanation and disables others–sometimes even preventing us from seeing the problems that need to be explained. Changing operating systems matters. For ten years, in fits and starts, that’s the kind of change that Re: has been after.

Hi Guys,

Very interesting discussion so far. Do any of you use the social annotation tool hypothes.is? I made some quick annotations as I read in case you do. They are public annotations of the report, but we could also create a private group if that more appeals. https://hypothes.is/groups/__world__/public

Lisa

I used it in a course last spring.Really great. This link gives me over 1M annotations. How do I find yours?

Best

John

Hi everyone,

I love revisiting this document, which at the same time speaks to this moment and to a rather different one. For instance, the language games of inter-, trans-, and de-disciplinarity feel rather dusty, then again, may they always were…. To my mind, they had their use 10-15 years ago, as tools for breaking up existing orders of knowledge, but it turned out they complete lacked the element of speculation and dynamism, the “knowing” that Geof and 2 x John discussed earlier in the thread. Hence, they were unable to serve as operating platforms for creating new and transformative knowledge futures. Today, interdisciplinarity (and all the others) are as effective rallying cries as Deconstruction!

But the passage that I was really interested in was this one: “Through its Exchanges, The Re:Enlightenment Project has been at work materializing a more inclusive and vigorous we—a collaborative we fueled by the diverse energies and expertise of different kinds of institutions.” Partly because I am not sure I we have really succeeded in that ambition. For sure, there have been moments when a “more inclusive and vigorous we” has manifested itself, during Exchanges and other events, like the Deutsch-Rees event that Cliff referred to above, but also at a much smaller scale, like in the back offices of the Norwegian National Library. But looking back, and over the long-term, I am not sure that we (whoever that is) has done enough to sustain and expand the “we” of Re:Enlightenment, to make it inclusive and vigorous enough. But I do think we have a chance right now, in preparing for the next New York event, to reflect on how such an inclusive and vigorous “we” could come about, like I think you discussed at the last meeting, which I missed. A “we” that includes more forms of knowledge or “knowing”, more sites and institutions, exactly as the Report envisions. The best (even the only) way of making that happen is to reach out to other people, some that have already participated in Re events, some that we don’t know yet, at least not all of us. Several of the Exchanges have had that kind of outreach, and I guess the question is how we can make the New York event serve that purpose – what the Report terms “materializing a we”.

The “we”-question is obviously a practical one, but also, interestingly, a theoretical one. Even though the Report calls for a “we”, the concepts and metaphors, like “operating platform”, “protocols”, “exchange”, “institutions”, “knowledge” (or “knowing”) leaves the question of agency open. I guess this works in two ways: on the one hand, it opens up Re:Enlightenment to anyone who is willing and interested in taking on any one of the designated knowledge tasks, or even mantle the more general knowledge ambitions; on the other hand, the same language makes it hard to insert oneself (or anyone else, for that matter) as agents of knowledge or knowing, or even contributors to Re:Enlightenment. As long as we are in the thick of it, I guess we can see ourselves both as agents and a “vigorous we”, but in the rear view mirror I find it hard to find a way back into ‘the knowing’.

Sorry for rambling at the end there. I might be an effect of Covid loneliness and the longing for an inclusive, vigorous, and not least, physical “we”. But for now our Zoom-meeting on Friday will have to do.

Nice Helge … and fully agreed on the inclusive ‘we’. In an ideal world (had we but world enough and time) I’d think of an exhibition space to attract and intrigue and engage some wider audiences.

I didn’t remember this document from 2011 (I thought I would’ve remembered the phrase “horseshoe of knowledge”), but it’s interesting because I’ve been writing about “the demise of the concordance,” and now I’m wondering if the seed was planted back then. I’m currently based at a humanities institute, and the document made me think about the day to day things that happen there. There are more social scientists around at the institute than there are here, I think. There actually isn’t too much hand-wringing about disciplinarity and interdisciplinarity. But there are certain activities people do together even virtually during the pandemic: the trading of article/book recommendations between scholars studying different things, collaborative writing/editing and writing groups, of course programming, and so on. The Re:E exchanges seem different, as there are usually different agendas than those at an institute. Anyway, just some thoughts.

As a relative latecomer to Re:Enlightenment (as Ryan shared in his last update, the Santa Barbara exchange was my first official contact with the group), I found reading the report to be a revelatory experience. I realize that, in retrospect, I’ve done my own archeology of the group, piecing together my understanding of what Re:Enlightenment is and what our goals are from conversations, communications, and exchanges: effectively, I’ve been using overheard fragments of this foundational document to reconstruct the original text that we now have in front of us. While, overall, the main themes of the report are the same as the ones that I’ve understood us to be working towards over the years, there are important parts of this document that haven’t been as apparent from subsequent meetings and exchanges that remain important for how we think through our goals. Though there are many of these that I’m eager to discuss, I’ll just touch on three of them in anticipation of our meeting on Friday.

1.

While I was struck by the similarities between the “operating platform” described by the original report, and the operating system that we are in the process of creating, a missing word, both then and now, seems to be “environment.” I was struck, reading through the report, by the proliferation of metaphors and descriptors that evoked the natural sciences. The crisis described by the report is occasioned by “funding streams drying up or changing channels”; the introduction of the digital is a “mutation” that requires the “evolution” of our sites of knowledge, which themselves are a “terrain” that we must traverse “without wandering into the desert of pure ungrounded speculation”; we have evolved an “organic forensics” that is tied to the “transactional or organic exchange,” etc. Environment is the concept that seems to lie behind these terms, both as a real-world object with its own sense of urgency, but also as it describes a set of external conditions in which something like knowledge can be situated. An environment comes with its own set of connections and relationships, an ecology, which exerts pressures on its inhabitants that force change, mutations, and evolution, and as the environment changes, it necessitates the exact kind of transformations described in the document. Crucially, it also connects to our use of “operating system.” In the understanding of human-computer interaction, we rarely interact with an operating system itself, which is the set of rules and protocols that translate our actions and programs into machine-readable instructions that can be interpreted by the hardware. Unless we’re running a developer’s build of Linux, we instead interact with a computing environment that allows users, applications, and programs written in different languages, to co-exist – to communicate across the divide between the organic and the mechanical. The environment is supported by the operating system but can actually exist across different operating systems as a middle ground in which the kind of exchanges described by the report can happen. In both senses, then, I think environment is a concept for us to hang on to.

2.

The description of the kind of interactions between different disciplinary configurations of knowledge that will be necessary in these exchanges is striking. The idea that we might operate in ways that are “opportunistic and strange, fraudulent or dilettantish” based on our traditional disciplinary backgrounds is strangely freeing. What are the limits of this kind of freedom in knowledge production? We are so used to accrediting our knowledge in very specific ways that it is hard to imagine what the alternative might look like. I’m thinking of the kind of rigor in statistical testing and the p-hacking that has occasioned the replication crisis in the social sciences, or the dense citational networks that act as a guarantor of creditability in the humanities. How do we assess knowledge without these apparatuses and what does this mean for the kind of knowledge that is created? The report seems to call for a revolutionary rejection of these traditional metrics that are based in a disciplinary site of knowledge production, but it is unclear about how we can replace them. Is this something that will evolve out of a new set of knowledge creation practices (a new environment), or is this part of the operating system that underlies the new set of practices (and therefore something that is predetermined)? The answer is unclear, but I think that figuring it out is a crucial prerequisite.

3.

What comes through most of all is the urgency of the tasks that the report lays out, an urgency that, I think, has only increased in the last decade. The environment of disciplinarity has continued to evolve in the ways that the report predicts, to exert new pressures on us and especially on the younger cohorts of scholars. I think that recapturing this urgency is especially important as we move towards the meetings in New York.

Great points Mark, I particularly like the idea of drawing attention to our environment in all the meanings of that word. On the computing side, we seemed to have moved to an ever more abstracted level, and now the environment that we do most of our knowledge production in is rather weakly known as the “browser”.

Your second point is vital too: the move away from institutions has costs, one of which is to unmoor us from familiar protocols of validation and authority. We probably agree that popular consensus alone is not a good test of knowledge, but even peer review is still a constrained form of consensus. In natural sciences, reproducibility is a key test of knowledge. What does reproducibilty look like in the context of a political, literary, or historical hypothesis?

Intrigued by the environment concept. . which as I read I first read as like Context. And as someone whose doctoral training was largely in Stanford’s Context center, I thought I grasped. But now–as your environment seems to be built, as well as received. . I am puzzling over questions of agency and purpose, of discipline-specific meanings, and of building blocks. . Good puzzles to play with, good tools to work with.

Mark, I’m intrigued by the important questions you ask. If memory serves Pete de Bolla’s master metaphor for the RE:enlightenment Project was that of an organism that could change and mutate overtime. But we also confronted the problem that the unity of our members did not seem to achieve the coherence of a single organism. We were a group of members speaking together but also occasionally disagreeing. It is interesting to think about environment as another way to describe the predetermined complex system within which we must function. But as Leslie says, we are also creating our own environment.

The 2011 report was certainly a stimulant for a lot of research I was doing at the time. So, it’s a good idea that Pete and Cliff have reissued it!

It calls for ‘a strenuous interrogation’ of disciplines. That is what I have kind of been doing but from a historical angle. There have been two sides to this approach.

Firstly, to look at the alternative forms of education which preceded the introduction of disciplines to get some handle on what were social and political impulses behind the introduction of disciplinarity.

Secondly, I have looked at the way in which disciplines are translated into curriculum and then embodied in the subjects.

Both of these approaches allows us to see the social and political impulses from which disciplinarity grew. I suspect if we are to do strenuous interrogation, we have to encompass some of these historical investigations.

This approach offers the tracing of disciplines through to actual practices and mechanisms, to where and how they are embodied in subjects, and also subject specialists? . . It can ferret out not only whose knowledge counts but who gets sorted into which knowledges, at the level of system as well as subject? . . . How much of that is Enlightenment history, and how much is layers of accretion over time? To keep the natural science imagery going–are Enlightenment knowledge rocks igneous or sedimentary? Did we find them–or are we building them?

Like a couple of others here, I have come to Re:Enlightenment after this document was written, and I don’t think that I’ve read it before now. Many parts of it are recognizable to me as ideas that bore fruit during the Concept Lab project. In particular, I hope that we went some way towards providing a method by which we can begin to describe and analyse conceptual forms using distributional concept analysis. We still have some way to go to convincingly depict these as realised forms that we might adapt and deploy (or that might even mutate themselves and escape from our lab).

I also recognise the discussion of protocols, which I think sits in an interesting relation with the role of computer science and related disciplines in this discussion. Computer science often struggles to locate itself, as it seems to be fundamentally about a methodological process, a particular kind of mathematics, rather than relating to the study of any specific part of the natural world or human life. In common with econometric methods, this lack of a particular focus can give rise to an illusion of objectivity. What the document above hits on correctly, I think, is that while the objects and the conceptual content of knowledge are inevitably situated, the processes and protocols of deliberation, and the venue or exchange where they are deliberated, are also necessarily situated — even if that is a different kind of siting to that of the topical content of the concepts (and acknowledging that the architecture of the concepts themselves also exert a force in addition to their content).

The core task of computer science is to design processes that to some extent have an agency of their own. Yet, at each stage, the choice of datastructure, algorithm, language, and physical machine constrains the outcomes, even before we direct a process at a particular dataset. When we think about a platform for an exchange of knowledge, perhaps where these choices are most evident (certainly in the last twelve months) are on media like this one: online texts ranked by conversation, recency, or voting. It is striking that these mechanisms are prevalent online, yet rarely explicitly debated. Should we direct attention to comments that are new? Or to those that are the most popular, as measured by votes? Some systems offer both upvotes and downvotes: in that case, ought we prioritise net popularity or the ratio (a proxy for degree of consensus)?

These are the everyday protocols by which attempts to produce knowledge are exchanged online everyday, but their design is usually left not even to computer scientists in general but often to product designers. What seem like niche process choices are actually implementations of core questions about the nature of knowledge production. How is consensus related to truth? Does new knowledge supersede old knowledge? Here is an article discussing some of the technical issues involved even in a system as apparently simple as average rating.: https://www.evanmiller.org/how-not-to-sort-by-average-rating.html

Systems that attempt to combine measures of recency, popularity, and controversy have even more involved protocols:

https://www.evanmiller.org/ranking-news-items-with-upvotes.html

It was fun revisiting the report that Cliff, Pete, and I wrote in 2011 for our London meeting. It has the energetic tone of a manifesto: urgency, the imperative voice, a call for change. It announces a chain of actors (in Latour’s sense) that mediate so as to advance knowledge: disciplinarity, platform, exchange…and the touchstones: past/present, technological change, de-disciplinarity and new connectivities. For my research for Protocols of Liberty, I found that the horseshoe offered a design principle that allowed me to gather heteronymous objects formed by different disciplines for studying the onset of the American Revolution. The key assumption here is that disciplines should not make, and investigators should not respect, proprietary claims. Instead, in the pan-disciplinary space of inquiry one can operate upon a larger, more inclusive, and more various set of objects. This is one way to lift the zoning restrictions of the disciplines. From my work with RE:Enlightenment Project, I’ve learned to value a broader sense of knowledge: the theory of lift enables the invention of the airplane wing that produces lift. Then ‘knowledge’ of lift is embedded in that object. In the same way, the odd and nonintuitive 18th century invention of ‘free speech’ made possible the popular declarations that embodied the political unity and corporate speech that make modern republics possible.

A great idea to come back to Re:read this report, to remember the discussions and debates that went into it. . and to see the discussions and extensions it provokes now. It holds up remarkably well—though between the language of crisis (financial) it invoked then, the sense of crisis (Covid and isolational) now –I do hope that by the NY gathering we might, maybe, be building on a bit of relief and re:newal?

I am also struck, in the report and comments, by the turns and returns to the issues of disciplines and Disciplinarity. Questions of the limits of Enlightenment (John S), attention to institutional forms and mechanisms (Aaron), possibilities of becoming obsolete (Aaron) or over (Mike), and the notion held in remarkable tension that disciplines are both fixed effects of the Enlightenment and always changing, in museums (Geof), subjects (Ivor) and fields, inside and out of academia (John B).

So we might want to think about ways to better map and track the change and stability of disciplines in both time and space. Something like Helge’s timelines? Or more like a lava lamp of emerging forms? If we look at the siting of knowledge mechanisms and institutional forms, we see a complex set of moving patterns where new tools might help us scale up our understanding.

In time: we have histories of Science (Geof) or of Subjects (Ivor) that show new disciplines created, established, fractured into separate bits (Physical and Social Anthro), or amoeba-morphed out of extensions (Neuro/biology). New fields work toward academic acceptance and departmental status (Business Schools); old ones wither away (Classics, Home Ec). But our available histories tend toward narratives of individual or tightly clumped disciplines, or contrast cases of binary pairings. Could we see the bigger environment?

In place: in undergraduate schools, and Arts and Sciences for example, Discipline and Department tend to be contiguous. But in other divisions of the University (Law, Business, Nursing, Education), disciplines are present—but not the only or even major organizing form. These schools look more like the horseshoe, with disciplines used to bring a particular lens on a common (kind of) subject. And outside the university structures, the mechanisms and practices are still more varied, the disciplines less prominent and less fixed.

Drawing on Campbell’s Fish-scale model of Omniscience, I tried long ago to speculate and draw (literally, by hand) a map of moving disciplines/subjects in high schools, back when interdisciplinary was a trend and English and History were being pushed to work together as Humanities. But across this group, we have substantially more knowledge of historical shifts and new graphic tools for far more elegant display, and even for dynamic mapping. Maybe that is a way of shaking off what Helge sees as ‘dusty’ efforts to lay out and break up existing orders of knowledge that just ended up reinforcing, or remaining ‘stuck?’

Image for comment above.

On re-reading Re:Enlightenment Report 2011

I haven’t participated for a while but I do recall RE EN 2011 and now, as then, my contribution will be from a more practical (and public) than theoretical perspective, largely in response to the report’s desire to be more institutionally inclusive/representational (ie not just the academy but the library and museum as well).

Over the past ten years, inter- or de-disciplinary (the eliding of boundaries in my work between history, material and cultural anthropology, history of collecting, art history, 18th century studies and digital humanities), the siting of knowledge in objects, and how knowledge is shaped (distorted, increased, left with absences) by databases have all had the greatest impact on my own making and receiving knowledge practises. More recently BLM and social media have also had an enormous impact on my work which forces me again and again to ask questions about, confront and re-interpret the dark side of the Enlightenment (slavery, imperialism, colonialism) then and now (pace new Sloane and slavery case in Enlightenment Gallery, August 2020:https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2020/aug/25/british-museum-removes-founder-hans-sloane-statue-over-slavery-links and https://thecritic.co.uk/issues/november-2020/opening-up-the-british-museum/). More on this at the end of this comment.